Sunday, September 24, 2006

My latest easytogrowbulbs order

Amaryllis White Christmas

Oxalis Grand Duchess Veriscolor

Ranunculus Flower Fields Collection

Those Amaryllis were only $3 per bulb, quite the bargain! I bought a dozen and will put them into my new bed along the walk in the side lot, next to the Amaryllis I found growing next to the house.

Biosphere Nursery & Seminole Springs Roses

- 2x Russelia: An interesting cultivar (or perhaps a species) of the Firecracker plant, with leaves that are oblong rather than fern-like. Nice.

- 2x Summer Cassia: I saw this grown as a standard at Leu Gardens this week. Lovely small tree, and someone recently called it "crack for butterflies."

- 2x Sparkling Showers Durante: I have the species of this plant, which has tiny lavender flowers. This cultivar has rich purple flowers that are dappled or striped in white.

- 2x (red) Milkweed: I brought home a Monarch caterpillar hiding out somewhere on one of these, but I fear the birds got it.

- 2x (bronze) Fennel: Beautiful plants, and a favorite of Swallowtails.

- 2x Confederate Rose: Why isn't this stunning plant grown more often? A member of the Hibiscus family (Hibiscus mutabilis). The blooms start out pale pink, almost white. By the end of the day, they're a rich cerise-pink. By evening they've closed and contorted themselves into tight whorls.

- 'Maman Cochet': "Orange-pink & orange-pink blend [op] blooms. Strong fragrance. 30 petals. Blooms in flushes throughout the season. " 1935.

- 'Maitland White' ('Puerto Rico'): Bermuda Found Rose. "White, near white & white blend [w] blooms. Sweet fragrance. Blooms in flushes throughout the season."

- 'Madam Lombard': Very double, pink-orange.

- 'Smiths Parish Yellow': "The ivory/yellow flowers sometimes yield a petal that is pink or red or perhaps displaying a stripe across the yellow. A tidy shrub with few thorns it's thought that like many of the Bermuda Mystery Roses it has a strong Tea influence. We have found that this rose performs fairly well in light shade."

- 2x Lavandula multifida

Plants For Texas® Texas Born, Texas Tested For Texas Gardens™

The plants offered on the Plants for Texas site are in almost all cases also appropriate for Central Florida, which enjoys the same deluge-drought cycle and intense sun of our neighbor across the gulf:

Every year gardeners go to their local garden centers and walk out with armloads of plants. After planting, mulching, trimming, watering, fertilizing, and generally babying the purchases they disappear. By July the only thing left of some of those plants is the plastic tag. Where do they go? Most likely they melted in the Texas heat. In many cases dead plants only came as the result of picking the wrong plant, Not having a "brown thumb".

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

But what of the lilies in the field?

You'll often hear about the importance of lavishing organic materials on the planting hole, amending the soil in a plant's future home with lots of organic material, bone meal, blood meal, kelp, fish heads, sacrificial virgins, etc. etc.

The idea makes sense, of course: We all know how important it is to have rich, humusy soil full of nutrients and capable of retaining moisture. So it makes sense, right, to mimic good soil by sparing no expense in improving the soil nature has provided with organic materials, etc.

However, as is usually the case with Conventional Wisdom, the seemingly-sound idea behind the $20 hole does not match reality. Quoting from the University of Florida IFAS-Extension literature:

A common procedure for transplanting container-grown plants involves amending the backfill around the root ball with an organic material such as peat. However, a significant amount of research over a range of irrigation schedules, plant materials, and soil types provides no evidence that this practice is beneficial. In fact, incidences where roots remain in the amended backfill soil and do not grow into the undisturbed field soil have been reported. The argument for amending backfill soils centers around the fact that peat increases the waterholding capacity of a sand soil. What actually happens is the water in the adjacent landscape soil is held at greater tensions than the water in the amended backfill. The result is a drying container root ball as water moves from the container medium and the amended soil into the adjacent landscape soil as it dries.Plants transplanted in very rich holes do not, as expected, thrive; instead they are actually harmed by the over-abundance of organic material. This is clearly an example of too much of a good thing, and a waste of money, at that.

I've known about this debunking for some time, but came across it again today while exploring UF's extension website, which offers a lot of sound gardening advice backed by a good dose of empiricism. I don't enrich my planting holes much, usually removing a spadeful of Florida "dirt" and replacing it with compost from my pile, a fork or two of peat, some ground pine bark, granular, slow-release fertilizer (Osmocote), some Milorganite (for a weak but quick boost of NPK) and, lately, some water-absorbant crystals. No pretensions for science or consistency. Whatever suits my fancy and whatever is at hand.

Then, lots of mulch.

In annual beds, I pull the mulch back, empty a couple of wheelbarrows full of compost and spread it evenly. Then I plant my seedlings in the compost, heaping the compost up into little, low mounds. The mulch goes back, and that's it.

The mounding serves two purposes: It raises the plants higher, so the mulch doesn't cut their stems. And, since everything sinks in Florida over time, it prevents the plants from being "drowned" or rotting from too much water. (This is the nature of an inert sandy soil: organic materials decay, but the sand does not.)

At least once or twice a year, for all my bushes and new trees (particularly for roses), I pull back all the mulch from the beds and put down a thick layer of compost and shredded leaves and a sprinkle of Osmocote. Then I push back the mulch.

I think this slow and dispersed amending of the soil, from the surface down, avoids the pitfalls of the too-rich hole while still improving the general health of the soil.

Landscape Mulches: Will Subterranean Termites Consume Them?

Little is known or mentioned in the literature about mulches and termites. Warnings about not leaving pieces of wood or stakes as termite attractants after house construction are common though. One publication noted that when construction is complete on a new house, every "piece of wood that can be picked up between the tines of a common garden rake should be removed"(Moore 1979). Another publication notes that moist warm soil containing an abundant supply of cellulose material is a termites optimal environment (Johnston et al. 1972). They define "cellulose material" as scraps of lumber, stakes, stumps, and roots left in the soil. One of the prerequisites for subterranean termites and wood-decaying fungi is for the wood to be in reasonably close proximity to the soil surface (Moore 1979) as mulch is. Yet, most houses in Florida with many trees and other landscape plants may already have plenty of food available for termites, and mulch may just be one more additional food source.

Further research on mulches and termites is warranted to determine if we should be concerned about using mulch around houses. Also, research is needed on possible repellent mulches such as melaleuca which might serve as an additional barrier for household protection against termites. At this time the benefits of mulches such as water conservation, reduced used of herbicides, and reduced soil erosion are very apparent while the risks to termite infestations due to mulches are unknown. Homeowners will continue to use mulches in landscaping around their houses and buildings. Our current recommendation is to be vigilant and up-to-date with termite inspection and treatment.

Monday, September 18, 2006

Commercial Floriculture

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Porterweed and a Zebra Heliconian

Drinking coffee, looking out the kitchen door, I saw this Zebra Longwing flopping about my garden this morning. I followed it for a bit as it flitted around my Blue Porterweed. For what I was trying to do—capture something in motion in filtered light—my aperture was too wide and my f-stop too slow, but it turned out a pretty cool effect. They're such slow-moving, easy-going butterflies (unlike most Swallowtails), it's easy to get a closeup shot, as I did below.

Drinking coffee, looking out the kitchen door, I saw this Zebra Longwing flopping about my garden this morning. I followed it for a bit as it flitted around my Blue Porterweed. For what I was trying to do—capture something in motion in filtered light—my aperture was too wide and my f-stop too slow, but it turned out a pretty cool effect. They're such slow-moving, easy-going butterflies (unlike most Swallowtails), it's easy to get a closeup shot, as I did below.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

Gardenias in September...

It's been an odd summer... Very dry, if you check the monthly averages. However,you wouldn't know it to see it: Longish periods of drought, then heavy rainfall right in the nick of time, greening everything up for a time, only to return to more dry weather. Instead of daily or near-daily rains, we've been getting one rain shower a week. South of us, say Sanford and down, has seen plenty of rain after a dry spring. North of here is just plain parched, with drought conditions in north-Volusia county.

It's been an odd summer... Very dry, if you check the monthly averages. However,you wouldn't know it to see it: Longish periods of drought, then heavy rainfall right in the nick of time, greening everything up for a time, only to return to more dry weather. Instead of daily or near-daily rains, we've been getting one rain shower a week. South of us, say Sanford and down, has seen plenty of rain after a dry spring. North of here is just plain parched, with drought conditions in north-Volusia county.Anyway, what with the odd weather, some cool breezes, and shortening days, many of my plants think it's springtime: Many of my orchids (dendrobiums and oncidiums, mostly) have spiked, and this morning I noticed a bloom on my Gardenia, which typically blooms the first week of May. Roses are budding profusely, and by the middle of October they, and many other plants in my garden, will have shaken off the doldrums of sub-tropical climes. In the evening, sitting blowing bubbles with my daughter, I can catch from time to time soft, cool puffs of air, promising more clement weather.

Zone 9 Tropical Plants

Zone 9 Tropical Plants - Offers Exotic Tropical Plants: Flowering and Fragrant Vine Shrub

Some of their offerings:

Jatropha multifida - Coral Plant (qt)

Bauhinia purpurea - Purple Orchid Tree (gal)

Bauhinia tomentosa - Yellow Bauhinia (gal)

Bauhinia grandidieri - Dwarf Orchid Tree (gal)

Duranta Sweet Memories (qt)

and some interesting Gardenias...

Thursday, September 07, 2006

My Trade List

I always have potted up for trade...

Stachytarpheta jamaicensis 'Porterweed'

Hamelia Patens 'Firecracker Shrub'

Star Jasmine

Rex begonia

Ruellia elegans

Alternanthera 'Purple Knight'

Numerous Old Garden Roses

African Purple Basil (awesome plant)

Blue-Eyed Grass (another winner)

Helianthus debilis 'Dune Sunflower'

Spicy Jatropha (J. integerrima)

Various keikis from Dendrobium orchids

Seedlings:

- Thunbergia alata (blackeyed susan vine)

- Pot marigolds (various vigorous cultivars)

Monday, September 04, 2006

Leu Gardens in September

I was struck by how different the gardens look at the end of summer from how it looks in, say, January: The camellias, azaleas, perennials,

and globulus citrus have all faded into a background, a canvas of green; in their place, front and center, a tropical vision of fringes and cups painted from a combustive palette of oranges, reds and yellows. The trip today reminded me—a timely reminder, amidst the doldrums of subtropical "fall"—that Central Florida is a special place for gardening: At 30° latitude, with a bit of stubborness and know-how, we can grow practically anything: Camelias, Azalaes, Orchids, citrus, Hibiscus, Rosa, bananas, figs, Delphiniums, Papaver, Daisies, Dahlias, Crotons... Where else are hard-pressed to decide when a garden looks best, December or August?

and globulus citrus have all faded into a background, a canvas of green; in their place, front and center, a tropical vision of fringes and cups painted from a combustive palette of oranges, reds and yellows. The trip today reminded me—a timely reminder, amidst the doldrums of subtropical "fall"—that Central Florida is a special place for gardening: At 30° latitude, with a bit of stubborness and know-how, we can grow practically anything: Camelias, Azalaes, Orchids, citrus, Hibiscus, Rosa, bananas, figs, Delphiniums, Papaver, Daisies, Dahlias, Crotons... Where else are hard-pressed to decide when a garden looks best, December or August?(Clockwise, from far left: Hibiscus schizopetalus, Ricinus communis 'Red Spire', Chrysothemis pulchella 'Black Flamingo', Caesalpinia pulcherrima, Rosa 'Pink Pet' (China, 1928), Rosa 'Fragrant Apricot' (Floribunda, 1998), Jatropha podagrica, Alpinia latilabris, Center: I have no clue.)

Saturday, September 02, 2006

The Sunshine State

If you've gardened for a while here in the Sunshine State, you quickly learn to be leery of the advice to plant anything "in full sun." Every newbie who's planted a geranium in June in full sun, because that's what he did in Jersey, learns that full sun is a death sentence for all but but a few plants. Aside from trees and some large shrubs, I'm hard-pressed to think of many plants that actually do better here in Florida in full sun than they do in high shade.

For instance: Even roses, plants famous for their love of sun, are taxed in June and July by noontime's glare. You'll read that roses need at least six hours of full sun and do best with ten, but that's for Yankees. Here in Florida, roses will thrive with just four or five hours of direct sun, especially if they continue to get some additional time of bright light. My main rose bed, where 'Prosperity', 'Don Juan' and 'Abraham Darby' compete for place of honor, gets about six hours of sun in June, and some bright light in the late afternoon. This amount seems pretty optimal. I have other roses, interplanted with herbaceous perennials, in a border that get ten hours of sun: They need additional water, and don't seem to do any better than their less-sunny comrades.

I could provide plenty more examples of plants famous for their love of full sun elsewhere that quite prefer a little shade here in Florida. So why is this? Why does "full sun" elsewhere, farther northward, so often mean "partial sun" here? Of course the answer is: The sun is just stronger here in FLA. But that's like responding to the question: Why does the train move? with the answer: Because the wheels turn.

Why is the sun stronger?

DeLand, where I live, is located at 29° of latitude, which makes it about two-thousand miles from here to the equator. (Each degree of latitude is approximately 70 miles. Traveling northward, two-thousand miles is roughly the distance between here and the Hudson Bay in Ontario. So, Central Florida is midway between the Hudson Bay and Columbia.) That relative proximity to the equator has a profound, positive relationship to the amount of insolation—the amount of radiant solar energy—any given point of earth receives.

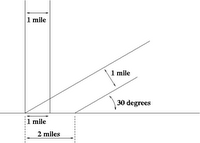

Of course, everyone knows that the equator is where the sun is strongest, where the day is more or less the same length all year long, and where there are no seasons. But returning to our earlier question: Why is the sun stronger at the equator? Largely, this difference is due to the axial tilt (23°) of the earth. The sun's rays hit the earth at a higher angle—more perpendicularly— at the equator than anywhere else on the planet. Twice a year (the autumnal and vernal equinoxes), the equator is directly perpendicular to the rays of the Sun: At noon on the equinoxes, the sun is directly overhead and the rays of the sun hit the earth perpendicularly. On those dates, at every point along the equator, the earth receives its greatest amount of radiant energy.

So, here's the rule: The closer one is to the equator, the more vertically the Sun's rays fall on the earth. The amount of radiant energy is directly correlated with the degree to perpendicular that the Sun's rays hit the earth: The closer to perpendicular, the great the radial energy. This correlation has to do with both simple geometry, and with atmospheric effects: When the s

un is at a lower angle (closer to the horizon), as it is the farther north one goes, a given point on the earth's surface receives a lower density of incident light. This difference in density of incident light is, fundamentally, similar to the difference in intensity between, say, early morning light an noontime sun. The higher the sun in the sky, the more intense the solar radiation, and the more solar energy made available to photosynthesis for conversion into sugar. Furthermore, the lower the Sun's angle relative to the earth, the more of the earth's atmosphere that the sun has to pass through.

un is at a lower angle (closer to the horizon), as it is the farther north one goes, a given point on the earth's surface receives a lower density of incident light. This difference in density of incident light is, fundamentally, similar to the difference in intensity between, say, early morning light an noontime sun. The higher the sun in the sky, the more intense the solar radiation, and the more solar energy made available to photosynthesis for conversion into sugar. Furthermore, the lower the Sun's angle relative to the earth, the more of the earth's atmosphere that the sun has to pass through.So, what's this all mean to the Central Florida gardener? The map to the right gives a rough idea of the difference in insolation: If you click it and look carefully, you'll notice that Central Florida receives, annually per day, about 25% more insolation, more kilowatts per meter per day, than, say, Boston.